By Steven Krolak

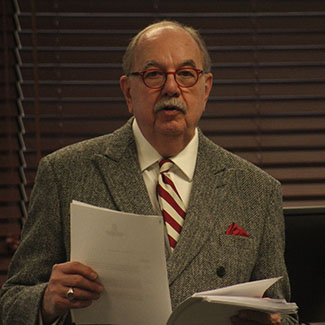

(NEW ALBANY, Ind.)—John-Robert Curtin, adjunct instructor of criminology and criminal justice, is from New England. Gentle in his delivery, yet he doesn’t mince words: The first assignment his students receive in CJ 313: Peace, Conflict and Social Justice is to write their own obituaries.

As a way for an instructor to hammer home the personal relevance of a course, a memento mori is pretty much unbeatable.

But beyond the shock value, the assignment encapsulates the philosophy and method of an educator who moves between academia and the “real world,” obliterating the line that can sometimes separate the two.

In the process, he has fostered a conversation that enhances both teaching and learning, to the benefit of students, who internalize the larger dialogue in a way that enables them to be at productive peace with themselves, and with the world.

The moving business

Curtin teaches a range of courses involving conflict management, ethics, mediation, restorative justice, business, and behavioral transition.

He likes to say that he’s in the moving business.

“We are assisting students of all ages to move to the next phase of their lives,” Curtin said. “It is my job to help them equip themselves with the necessary skills and tools to make a successful transition.”

Those skills and tools include competence in effective listening and communication, knowledge of the sources of conflict, the ability to differentiate between different mediation processes, the ability to demonstrate ethical standards, and perhaps most importantly, the capacity to understand their own unconscious biases.

His methods include lectures, group discussion, mediation simulations and role plays, alongside readings and videos. Students also participate in practice mediations, receiving individual feedback from Curtin.

At the core of Curtin’s philosophy, reflected in his lessons, is a conviction about the human condition.

“Humans were designed for cooperation and interconnection,” Curtin said. “So I spend time at the beginning of each class helping students to understand that their interconnection with others is vital if they are to truly understand the nature of human beings.”

To spur discussion, Curtin begins his classes with four basic questions:

- When did we as human beings begin to think of some other human beings as disposable?

- Is punishment the only way to control negative behavior?

- Is it possible to hold another human being accountable, or should the purpose be to help others personally accept accountability for their actions?

- What is the nature of the world and what is my personal role in the world?

The discussions that emerge, like the obituaries, compel students to confront their fundamental world views.

In the criminal justice context, this means questioning the very concepts of “criminal” and “justice”. It means sacrificing any notion of a cut-and-dried outcome — based on what Curtin calls seeing other humans as disposable – to a messier but more honest and compassionate vision of a very nonlinear process of improvement.

“Criminal justice students need to understand more than policing, courts, and corrections,” Curtin said. “They need to understand the nature of human beings and our need for connections to each other, and they need to understand that society cannot continue to believe that some people are disposable.”

To dispose of people is to avoid a conversation that not only resolves conflict, but forces us to define our own humanity. It is the ultimate cop-out. By challenging students to remain inclusive, Curtin also gives them the opportunity to solve, rather than evade, tough decisions, even if that can only be accomplished by altering one’s own point of view.

“By the end of the class students will know a great deal more about themselves than they ever have before,” Curtin said. “They will think critically about their assumptions and judgements and will understand that they have an obligation to test their assumptions before acting upon them.”

States of being

“The skills needed to be an effective mediator are also life skills to be an effective professional, spouse, friend, colleague, neighbor,” Curtin said.

He arrived at this conclusion by living life, and confirmed it through academic accomplishment.

Raised in a small seaside town in Rhode Island, he advanced through various trades, spurred by curiosity and his knack for being at the right place at the right time, and recognizing both as such. He studied poetry, yet opportunity pushed him in another direction, and in the early 1980s he became the youngest director of a PBS affiliate station in country. He moved to Louisville to lead WKPC-TV, and when that station merged with Kentucky Educational Television, Curtin entered a transition. He launched the Connected Learning Network, to produce online learning resources for colleges and universities. One of those modules, on bullying, opened the door to the next chapter in his life.

As Curtin delved more deeply into the field, he recognized the need for more formal expertise, and earned a doctorate from the University of Louisville with a dissertation comparing anti-bullying statutes in different U.S. states.

He then founded 4Civility Institute, which provides best-practices skill sets, reporting tools and training in techniques to deal constructively with conflict, to correct and build proper relationships and to move all participants to improve personally and professionally.

To date 4Civility has offices in Louisville and Dublin, Ireland, and has worked with entities in the U.S., Barbados and several European countries.

All of that experience funnels into the classroom experience at IU Southeast, which resembles a professional workshop that he might offer to a group of corporate executives or to the leadership of government agencies.

While applicable in any field, his expertise is especially valuable for students of criminal justice, who deal with conflict in a very real way, as a core part of their field.

For Curtin, conflict is an inevitable feature of life. But how we handle conflict determines positive or negative outcomes for us as individuals, and for our society.

Over the years, Curtin has refined his vision of human awareness and behavior into “Seven States of Being.” This forms the theoretical framework of his approach.

The states—mental, emotional, physical, transpersonal, values, ethical, historical—are aspects of our personal existence that we encounter in everyday interactions. Each of us has the potential to express these states positively or negatively, depending on our level of self-awareness and degree of control. Ideally, we understand ourselves and others, and exhibit a positive stability.

“When one does not have positive control over one or more of the seven states, there is a tendency to compensate for the lack of control, typically with negative thoughts, actions and deeds,” Curtin said. “Control is then established through conscious or unconscious rationalization as justification for negative behavior.”

While the need for a sense of control is universal and foundational for our comfort in the world, Curtin maintains, if it not coupled with a sense of connection to oneself and others, it will become destructive.

“The road to insanity is paved with rationality, fantasy and paranoia,” Curtin said.

Emotional intelligence, on the other hand, fosters empathy and ultimately compassion.

With this theoretical framework, students come to understand the reasons for their own choices, and the choices of others.

Further exercises, such as those in Curtin’s portfolio assignment, task students with a variety of activities that call for reflection and re-orientation.

They must compile a list of strengths and weaknesses, then compare it with how others see them. They must show appreciation to both strangers and those in their orbit, and reflect on how it felt and how the other people reacted. They must ask themselves difficult questions like, “In what ways are the advantages I experience disadvantages for others?” and “What am I afraid of when I am angry?” They must generate a list of ten to 15 ways that empathetic listening might change the outcome of a conflict-prone situation. In these and many other exercises, students learn to understand their own approach to conflict, and to find ways to make it more constructive.

The benefit isn’t a world without conflict, but a world in which individuals who understand themselves also understand how to address that conflict.

The root of civilization

Criminal justice isn’t the division of the human community into two groups, the criminal and the just. It is in many ways a dynamic and ongoing conversation between intention and action and the community standard of acceptable behavior as enshrined in law.

In Curtin’s view, self-awareness is the root of empathy, which supports compassion, which is the key to being a good citizen.

For students, the value of this process transcends the course, touching every aspect of their personal and social behavior.

“If we follow this logic we come to a place where we see the concept of civility being truly essential to concepts of compassion, dignity, justice, fairness, and democracy,” Curtin said. “We come to a place where civility truly becomes the root of civilization, and a civilized society.”