By Steven Krolak

(NEW ALBANY, Ind.)–In a first-of-its-kind for research, printmaking student and IT support staffer Kathryn Combs is using eye-tracking software to examine how audiences look at art, and to produce works that span the gulf between art and technology.

And it all started with deodorant.

Two years ago, as Combs strolled through a local mall, she was invited to take a survey for a market research firm. The in-kiosk quiz used eye-tracking software to gather information on where Combs’ attention was focused when she looked at an image featuring a shelf of different deodorants.

The data provided by her darts and stares would be used to sharpen the effectiveness of promotional graphics for the firm’s client. Combs, ever the artist, immediately saw the potential for creative work with a less mercenary purpose: to create works of art that would incorporate the reaction of the viewer.

Working with Susanna Crum, assistant professor of art in printmaking, Combs submitted a proposal for the project, Looking Longer, that was awarded a student summer research fellowship this last summer.

The project essentially recreated Combs’ mall experience, with a few significant twists, and a deeper import. Where marketers use eye-tracking and mouse-tracking to gain data that allows them to analyze and optimize advertising, Combs’ project sought to create images that encourage viewers to reflect on the way they look at art.

To Combs’ knowledge, it’s the first such application of eye-tracking technology of its kind.

Having needs that were not met by readily available software, Combs downloaded two freeware programs—GazePointer and Fake Heatmap Generator—and molded them into a tool that would enable her computer to capture and track eye movement and translate it into heat maps at a resolution sufficient for printing.

To do that, Combs relied on her IT skills and work ethic, spending time researching and acquiring the knowledge that would enable her to overcome the limitations of each program.

This combination of artistic sensibilities and tekkie chops has been a theme in Combs’ life since she can remember. Her grandfather repaired and built PCs as a hobby, her mother painted while working as a help forum moderator. Combs great up liking both worlds, and sees them as related. She found this harmony respected at IU Southeast, where she took inspiration from the words of former Design Center director, Jonathan Ruth, who encouraged her to see both technology and art as problem-solving.

“If you’ve learned to problem solve creatively, you’re always looking for ways to fix or communicate something,” Combs said.

Armed with the right technology, Combs moved on to the art.

The next step was to select images that were in the public domain (free) and visually compelling. Combs knew from her research that portraits would yield almost identical heat maps, as the viewer’s gaze inevitably seeks out that of the subject. So she selected images with varied subject matter and more diffuse centers of interest, from diverse cultures and featuring a range of colors: a self-portrait by Van Gogh, a waterfall by Hokusai, a landscape by Rivera, a flower by Redon, and more. Combs intentionally drew from the creative commons, both to save money and more importantly, to respect the rights of fellow artists.

She then invited 15 volunteers—mostly friends and acquaintances—to spend a few minutes looking at roughly ten works of art. There were different selections for each person. (At this point, it was hard to tell whether this was a behavioral experiment, a computer science dry-run or an art project.)

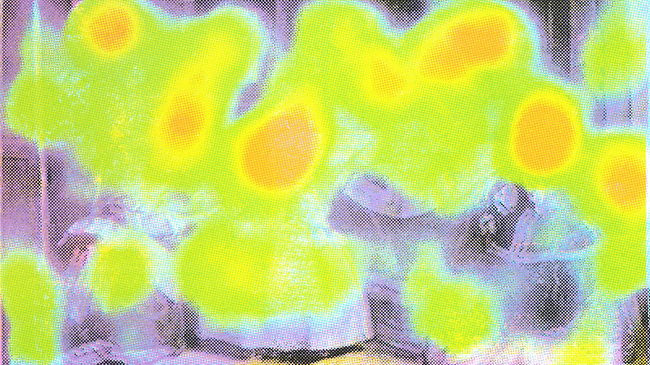

As they scanned the art, the computer tracked their gaze. The software created a heat map from their eye movements, showing where they had looked, and for how long.

Combs then printed a selection of the most striking images via silk-screen.

The choice of printing medium was not automatic. Initially Combs considered large digital prints, but decided on screen printing, as it aligned more closely with the philosophical purpose of the project.

“There is a rich commercial history with screen printing—it was one of the very first techniques for printing posters and flyers, so most people are familiar with it,” Combs said. “Using the commercial applications of screen printing and heat mapping to show one person’s view of art was interesting to me.”

Combs selected a group of prints, named them after the corresponding “test subject,” and presented the results in a gallery show at the SpaceLab.

The heat maps have a beauty all their own, inhabiting a realm reminiscent of ultrasounds or x-rays, a revealing of mind through attending. And this is the counter-intuitive conceit of the project, since art is generally perceived to be an active agent that comes smashing into a passive observer. In Combs’ project, the roles are reversed. Viewing is active. The final products, the two-dimensional screen-prints, are more than a documentation of viewing habits. They are recordings of a dialogue without words. This is art taking place over time. So although this is two-dimensional print, it shares that living quality with music and theater.

“I’m not aware of another project that uses this software to create artwork,” said Crum. “Kathryn uses it as a tool to better understand how individuals viewed popular images of art from art history, and to recreate those images layer by layer through the screen printing process—she’s really engaging with the medium on both a technical and conceptual level, which is an ideal, advanced approach for an art major entering her senior year.”

Michelle Clements, program analyst in the Office of the Registrar and a longtime friend of Combs, was invited to participate in the project.

Technically inclined, she was drawn in by the concept, then impressed by Combs’ masterful command of every aspect of the process, from managing the viewings to providing refreshments and activities for the waiting participants.

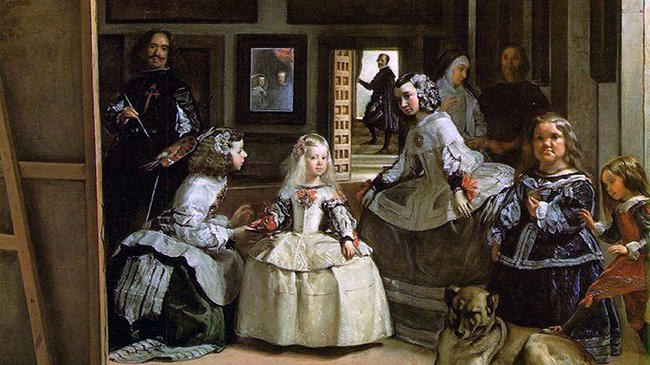

It turned out that one of the paintings Clements viewed was “La Meninas” by the Spanish Baroque master Velasquez. True to the intent of the experiment, the viewing unlocked different levels of experience for Clements.

“I saw this painting in person, on a trip to Spain when I was 16,” Clements said. “The guide at The Prado explained how it was unique for its time, with its complicated perspective, so I’ve always felt a connection to the painting, and when I saw it on the list, all those memories came flooding back.”

A detail of “Las Meninas” by Diego Rivera de Silva y Velasquez.

Michelle Clements’ personal heat map of “Las Meninas.”

While the project is unique as a way to deepen the experience of viewing art, and pathbreaking in its use of eye-tracking technology, it has also delivered results that validate traditional theories of art, demonstrating the attraction of viewers to the human face and warmer colors, for example, and showing how composition works to manipulate and channel a viewer’s gaze, essentially leading them through the “story” of the painting.

In many ways, Combs’ project displays in microcosm the same thoroughness and professionalism that marks her approach to art as a career. On the level of her creative work, she has taken to print in part because of its almost need for almost obsessively detailed planning. But she has also zoomed outward to initiate print exchanges with other artists from around the country, a networking venture that supplements her efforts on social media forums and in person at local exhibitions, as well as print conferences as close as last year’s event at IU Southeast and as far away as Atlanta, Ga.

For an artist like Combs, thinking outside the box is a survival skill.

“Artists have to wear a lot of hats—on any given day they may need to cold-call someone they’ve never met, juggle project deadlines, read and understand gallery contracts, promote a show, not to mention actually work on their art,” Combs said. “Being able to switch modes from artist to business person makes life easier, and helps build a reputation in the art community that you are reliable and professional, which is valuable currency in any field.”