By Steven Krolak

IU Southeast assistant professor of fine arts Emily Sheehan is fond of saying, “Drawing is thinking.” That linkage lies at the core of her approach, known more academically as cognitive drawing.

Last fall Sheehan shared her method and vision with a group of scholars and artists from around the world in a master class at We All Draw, an international interdisciplinary symposium in London, UK.

The symposium explored a basic question: What happens when we draw?

For Sheehan, exploring the question was an opportunity to take another step in her evolution as an artist and teacher, gaining cutting edge insights to enrich and enliven the classroom experience for her students.

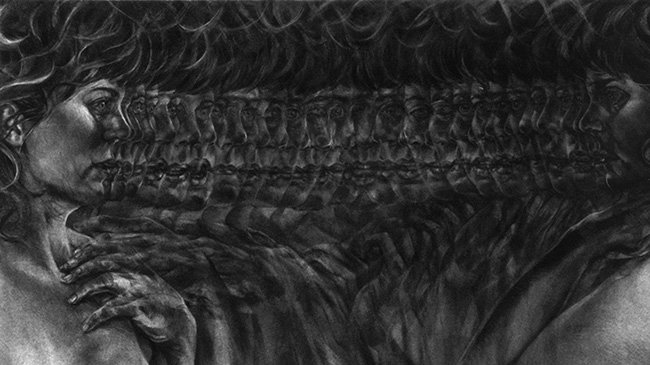

Emily Sheehan, “I keep telling myself,” 2014

We are what we draw

Sheehan’s interdisciplinary approach blends a dedication to traditional training in drawing with neuroscience and phenomenology, the branch of philosophy that investigates how we know what we know.

The drawing part begins with the human form as a mechanism of mass and movement. Sheehan is dedicated to the process of observation and rendering as handed down through artists and instructors such as George Bridgman, who in works such as Constructive Anatomy laid out the geometry and the mechanical operations of the human body for artists. Constructive Anatomy renders the human form as a series of interlocking blocks, spheres and wedges that, when properly related, suggest weight, volume, tension and even emotion.

“This is the basis of everything,” Sheehan said.

Emily Sheehan, “Moving forward” (detail), 2013

But drawing can be more than just rendering reality, according to Sheehan. It can also be an act of perception – of time, space and ourselves.

Taking a cue from the French philosopher of phenomenology, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Sheehan’s work explores the idea that we don’t actually perceive ourselves, but an image of ourselves. Thus drawing, especially self-portraiture, is an explorative process that can enable us to more fully experience ourselves and shape our self-perception.

In “Moving forward” (2013), Sheehan reveals her legs and feet in motion, capturing not only those parts of the body, but their transitions in space and changes in contour.

Alongside tools, our earliest records of human ingenuity are drawings. Speech, the supposed defining element of our species, is inferred from social organization. But drawing is a form of communication as well, and perhaps just as fundamental to understanding who we are.

“Drawing is an essential part of what it means to be human,” said Sheehan. “Self-representation is, as far as we know, is unique to our species. In drawing, we experience life more deeply. Possibly it’s the key to communication, the basis of our social organization and hence the key to our success as a species.”

Time and space

To Sheehan, drawing is more than illustration, and more even than self-discovery. It’s a way to experience time and space.

“Drawing can be a means to recognize and describe a process or progression in a way that you can take it apart and reform it,” she said. “It is both directional and instructional.”

Sheehan’s drawings don’t just sit there on the page. They unfold in time and space, and from multiple points of view, including that of the subject. They embody the movement of walking, the process of talking. They are more like theater – heard as well as seen.

In “I keep telling myself” (2014), Sheehan captures herself in the act of speaking the title, creating a zoetrope-like effect that ultimately becomes what it seeks to represent.

At the end of the day, drawing a human body is not just creating a two-dimensional representation of a figure. It is telling the story of the process of seeing that figure, and of creating that representation.

Sheehan’s work reminds us that the interactions between artist and model, and finished drawing and viewer are dynamic events that happen in time. The experience of art, from the initial concept to the viewing, is an event that leaves all participants changed.

Some of the most acute and important changes take place within the artist. Since the act of making art records an experience, the question becomes: Does drawing contribute actively to the shaping of our perception of reality, on a neurological level?

Does drawing shape the brain?

At the forefront

Sheehan and other We All Draw participants were intrigued by cross-disciplinary conversations that relate art to neuroscience.

“The brain responds to motor recognition,” Sheehan said. “It seems that connecting pencil to paper leaves a trace, and the trace allows the brain to re-access information in a different part of the brain, which can then connect to memory, reason and other facilities.”

In some respects, this process resembles writing, and according to Sheehan, it is not clear from the work presented if drawing is more or less efficient as a means of transforming information into a symbolic system and means of communication.

The conversations at We all Draw may sound esoteric, but they have direct relevance for the emerging partnership between the arts and so-called STEM fields.

Over the past decade, a number of initiatives funded by the National Science Foundation and others, and led by organizations such as the Art of Science Learning, have documented the significant contribution that arts-based learning can make to creative problem solving, innovation and collaboration, skills necessary to succeed in science, business and other fields traditionally not associated with the arts.

The results are so compelling that for many, STEM is rapidly becoming STEAM — Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics.

“When drawing functions as a means to develop and represent understanding, it can be used to bridge perceived educational gaps,” Sheehan said. “For example, there are correlations between reading difficulties and struggles with connecting to math and science in STEM fields. If we can find methods to visualize and use drawing to access information, those deficits can be minimized.”

What happens when we draw?

A lot.